Ok, Who Brought The Knotweed to Vermont, Why, And Now What?

Ironically, one of the early justifications for planting knotweed was to stabilize riverbanks. The reality is the opposite.

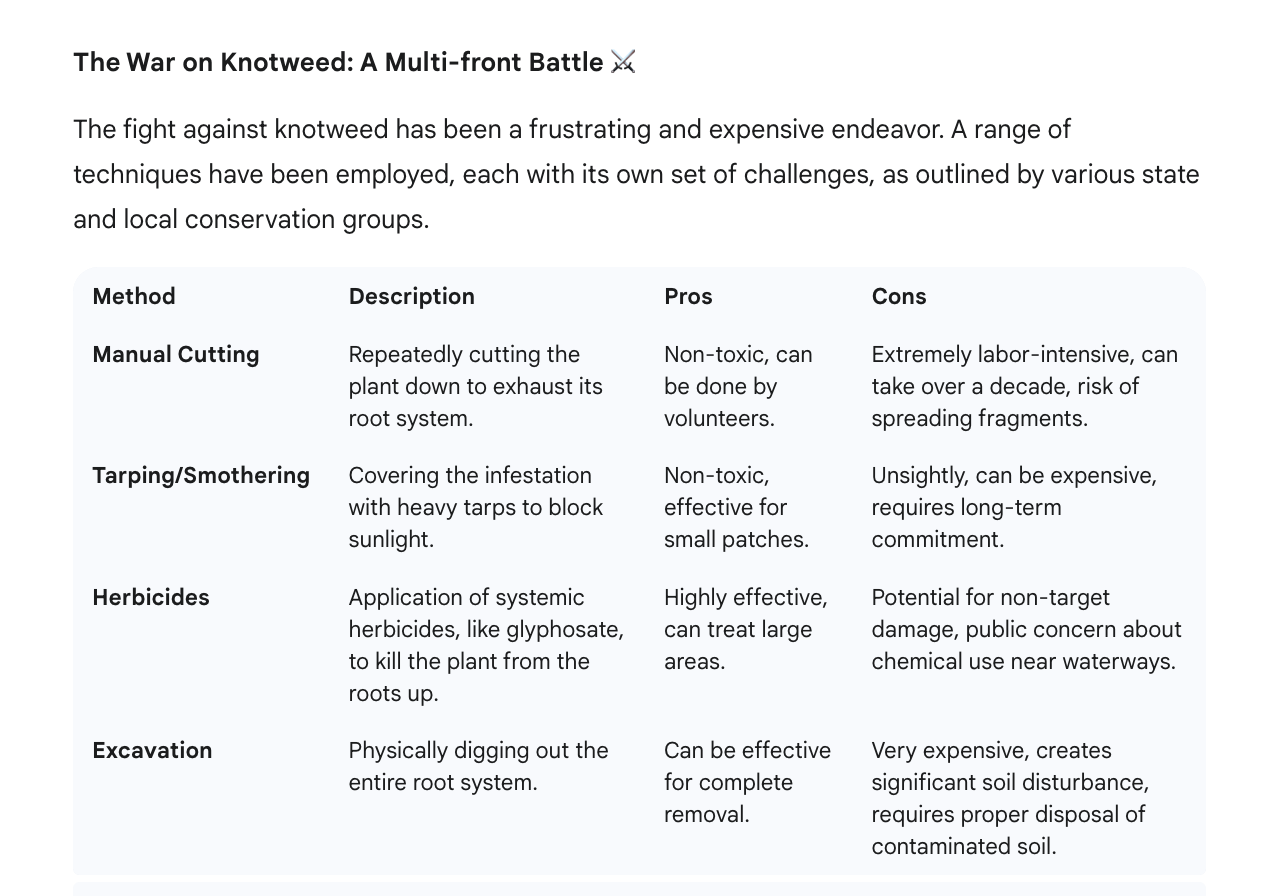

On the winding banks of the Mad River, a new team of environmental stewards has been deployed. They’re tireless, work for food, and are surprisingly adorable. They are, in fact, goats. In a landscape scarred by a relentless invasive plant, the communities of the Mad River Valley are placing their bets on a quartet of these four-legged "goatscapers" to reclaim their riversides from the grip of Japanese knotweed. As reported by the Valley Reporter, this novel approach is the latest chapter in a long and frustrating battle against a botanical invader that has rewritten Vermont's riparian landscapes.

The Green Menace: What is Japanese Knotweed? 🌿

At a glance, with its heart-shaped leaves and bamboo-like stems, one might mistake Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) for an attractive ornamental. But for those who know its true nature, it’s a green monster. According to VTInvasives.org, this herbaceous perennial, native to East Asia, is one of the world's most invasive species. It forms dense, light-blocking thickets that can grow over 10 feet tall, crowding out native vegetation and creating an ecological dead zone. Its root system, a sprawling network of rhizomes, is notoriously aggressive, capable of exploiting cracks in pavement and building foundations.

How Did Knotweed Get to Vermont

So how did this botanical bully get here? VTInvasives.org also notes that Japanese knotweed was introduced to North America in the late 19th century as a prized ornamental and for erosion control and riverbank stabilization.

By the 1890s, it was being sold in American plant catalogs and had established populations near Philadelphia, PA, and in New York and New Jersey. By the late 1930s, the plant was already recognized as a problematic pest, a trajectory that closely mirrored its invasion of the United Kingdom, where it had been introduced in the 1840s and is now officially designated as the country's most pernicious weed.

Its rapid growth and attractive appearance made it a popular choice for gardens and landscaping. However, its escape from cultivation was swift and its spread, relentless. The plant’s ability to reproduce from tiny fragments of its roots and stems means that a small piece, carried by a flood, a lawnmower, or in contaminated soil, can start a new infestation.

In Vermont, the problem reached a terrifying tipping point after Tropical Storm Irene in 2011. The storm's historic flooding tore through river valleys, scouring banks and carrying knotweed fragments downstream. In a 2023 reflection on knotweed published in the Valley Reporter, a University of Vermont intern noted the significant infestations in the Mad River Valley and the work being done to care for the health of the waterways. In the storm's aftermath, knotweed exploded along the state's waterways, colonizing the newly disturbed and sediment-rich soils.

The Statewide Scourge and a Failed Promise

Today, Japanese knotweed is a grim fixture on the banks of most major rivers in Vermont. While precise data on the total acreage of infestation is hard to come by, the Missisquoi River Basin Association reports that knotweed covers "miles of river front property in Vermont."

Ironically, one of the early justifications for planting knotweed was to stabilize riverbanks. The reality is the opposite. A 2021 study highlighted by the Invasive Non-Native Specialists Association (INNSA) confirmed that the presence of Japanese knotweed is associated with a significant increase in soil erosion. The shallow, dense root system of knotweed offers little real stability. In the winter, when the plant's canes die back, the soil is left bare and vulnerable. This leads to increased erosion, which in turn degrades water quality and harms aquatic life. Furthermore, the towering stands of knotweed create a physical barrier, diminishing access to rivers for fishing, swimming, and other recreational activities that are central to Vermont's culture and economy.

The Mad River's Four-Legged Solution 🐐

Frustrated by the limitations of conventional methods, the conservation commissions of Warren, Waitsfield, and Fayston, with support from Friends of the Mad River, decided to think outside the box. Enter "The Mad Goat, LLC," a local enterprise providing the goatscaping services. As detailed in the Warren Conservation Commission's 2023 knotweed report, the project is a collaborative, tri-town effort. The concept is simple: the goats' voracious appetite for knotweed leaves and young shoots weakens the plant over time by preventing it from photosynthesizing and replenishing its root reserves.

Is it working? The initial results are promising. Jito Coleman, chair of the Warren Conservation Commission, told the Valley Reporter that after the first season of grazing, the knotweed in the targeted areas was significantly shorter and less robust. The project, now in its second year and bolstered by a recent $100,000 grant from the Lake Champlain Basin Program, is seen as a more natural and community-centric approach. While it’s understood that the goats are not a silver bullet—eradication will likely require several years of grazing and follow-up management—the project represents a hopeful shift towards more sustainable land stewardship.

Recommendations for a Knotweed-Free Future 🏞️

The battle against Japanese knotweed is a long-term commitment that requires a coordinated effort. Based on best management practices from the Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation and other experts, the following actions are recommended:

For Landowners: Early detection and rapid response are key. Learn to identify knotweed and remove small infestations before they become established. Be cautious when moving soil, as it may be contaminated with knotweed fragments.

For Community Groups: Follow the lead of the Mad River Valley. Collaborative, community-based initiatives can be highly effective. Pool resources, organize volunteer cutting events for small patches, and explore innovative, non-chemical control methods.

For State Agencies: Continue to support and fund regional invasive species management efforts. Invest in research on the long-term effectiveness and cost-benefit of various control methods, including biocontrol and conservation grazing. Public education and outreach are also critical to preventing further spread.

The story of the Mad River goats is more than just a charming tale of eco-friendly weed control. It’s a testament to the resilience and ingenuity of Vermont's communities in the face of a formidable environmental challenge. While the war on knotweed is far from over, the four-legged guardians of the Mad River offer a hopeful glimpse of a future where humans and nature can work together to heal a wounded landscape.

It's widely used as a valuable and nutritious food source in its lands of origin. Medicinally, too, I believe. WHY don't we do the same? Many "pest" species are a godsend when actually used. Dandelions, bamboo, Japanese knotweed: they all become problematic WHEN WE DON'T USE THEM.